Fall is fast approaching and schools are back in. What better thing than an educational post that finally answers all of your frequently asked questions? Prepare for lots of reading.

The Anatomy of the Hive.

The hives you are used to seeing in the fields are made up of wooden boxes and were designed in the 1880's. Not much has changed since then. Each box has 8-10 frames in it. The frames I use have a plastic foundation on them that has hexagonal imprints on either side that the bees build their wax honey comb on. These hexagonal cells (the hexagon is the structural form that provides the most strength using the least amount of material) are used by the queen to lay her eggs in and by the workers to store nectar and pollen in. The cells are built on a slight upward angle so that the nectar does not flow out. The bottom box of the hive is called the brood box and most of the eggs are laid there. Some may be laid in the next box up which is called a super. All the boxes further up are also called supers and if they are primarily for honey, they are called honey supers. There is an entrance at the bottom for the bees and it can be reduced depending on weather etc. My hives have a top entrance as well which helps ventilation of the hive.

Here is a diagram of an exploded hive from Storey's Guide to Keeping Honey Bees:

|

The Bees:

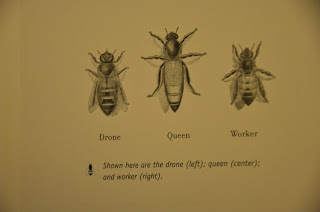

A hive is made up of one queen, a few hundred drones (males) and many thousands of workers (females). Hives can have up to 60,000 to 100,000 bees when mature...mine are might be between 20,000 and 30,000 bees right now but I'm not really sure. Here are the 3 bees that make up the hive.

As you can see, the queen is twice as large as the worker. She is an egg for 3 days, a larvae for 5.5 days, a pupa for 7 days and can live from 2-5 years. She is capable of stinging more than once but generally only uses her stinger to sting rival queens. The queen only leaves the hive once (except when swarming) and that is to be fertilized. She will not be fertilized by any of the drones in her own hive which ensures diversity of genes. The queen will leave the hive when she is born and will fly to a meeting place where all the drones from other hives also congregate and wait for virgin queens to come along. The queen will fly high above the meeting place and the the drones will follow. As she flies higher and higher, the weaker drones will fall off and only the strongest will continue and finally win. The queen can be fertilized by up to 17 drones so she will have diversity of sperm at her disposal. Each drone that was successful in fertilization will die since their sexual members literally get ripped out by the act. The queen then goes back to the hive and lays eggs for the rest of her life. She can lay up to 2,000 eggs per day and can choose which sperm will fertilize which egg. I even noticed in my own hives that the bees being born looked different throughout the season as they came from different fathers. From my reading and meeting other beekeepers I have heard stories of the queen laying more aggressive bees in response to attacks on the hive by skunks or racoons! The queen produces a pheremone. This pheremone lets the bees of her hive know where they belong and they will always come back to their own hive due to the pheremone. The workers also spread this pheremone around.

The drone is the male family member. He is an egg for 3 days, a larvae for 6.5 days, a pupa for 14.5 days and can live from 40-50 days. The drone is incapable of stinging. He has a great life generally. He eats, sleeps, is cleaned up after by the workers and makes flights every afternoon in search of virgin queens. If unsuccessful, he comes back to the hive to eat, sleep and be cleaned up after until fall. He is then booted out of the hive to perish in the wilds. More on this fate in another post. Some writings suggest that drones are the cheerleaders of the hive and keep morale up so perhaps they are not so useless as some suggest. My drones are black bodied and quite large. When they are flying in or out, you can hear their buzz...a very loud drone.

The worker is exactly that...a female worker who literally works herself to death. She is an egg for 3 days, a larvae for 6.5 days, a pupa for 12 days and can live 6 weeks in the summer and 6 months in the winter. The worker can sting only once. If she should use her stinger, it will rip out with her entrails and she will perish. She has 4 glands. One produces wax, one royal jelly, one invertase and one for scent. Her 6 weeks of life in the summer are spent in various roles. When she is born she immediately starts to work as a house bee. As a house bee she performs the following tasks: cleaning brood cells, attending the queen, feeding brood, capping cells, packing and processing pollen, secreting wax, regulating temperature and receiving and processing nectar into honey. When she is in her prime, around 3 weeks she moves on to being a guard. The guards do not let any bees or other insects not belonging to the hive in They will attack and fly away with any strangers unless they are carrying pollen or nectar. In that case they are welcome. Drones from any other hive are also welcome. I watched my guards attack a bumble bee and drag it away from the hive. It was easily triple the size of one honey bee. After being a guard the worker then moves on to being a forager, a very difficult and dangerous task. The foragers go out into the wild in search of nectar and pollen. They get a little help from the scout foragers who go out ahead to discover the best sources of nectar and pollen. As young foragers, they fly out of the hive and hover for awhile as they check the position of the hive (set their GPS). They hover, fly a little ways away, fly back, fly further and further until they are ready to set out. I have seen the new foragers hovering around the hive like a cloud, turn to face the hive and then head out. I imagine that the honey bees in my own garden are the young ones who aren't quite ready for the railway tracks. Foragers simply wear themselves out with flying and carrying nectar and pollen back to the hive. Weather, birds, wasps and pesticides are some of the dangers the bees have to contend with. Happily, London is "pesticide and herbicide free" so urban bees have a better chance of it. The workers that are born towards the end of the summer are Winter bees and tend to be fatter which helps them adapt to the cold better. They will live through the winter through to spring.

This is the end of Part I of the Educational Post. Stay tuned for how the Queen is made, swarming, making honey and other interesting facts!

No comments:

Post a Comment